-

Language:

English

-

Language:

English

Red Hat Training

A Red Hat training course is available for Red Hat Enterprise Linux

Overview of Containers in Red Hat Systems

Overview of Containers in Red Hat Systems

appinfra-docs@redhat.com

Abstract

Chapter 1. Introduction to Linux Containers

1.1. Overview

Linux Containers have emerged as a key open source application packaging and delivery technology, combining lightweight application isolation with the flexibility of image-based deployment methods. Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 implements Linux Containers using core technologies such as Control Groups (Cgroups) for Resource Management, Namespaces for Process Isolation, SELinux for Security, enabling secure multi-tenancy and reducing the potential for security exploits. All this is meant to provide you with an environment to producing and running enterprise-quality containers.

To help you get started using containers, this guide lays out key elements of Linux Containers as they are implemented in Red Hat systems. It also helps understand containers by contrasting them with similar technologies, such as virtual machines. Once you have a grasp of the general features of containers, you can try out a variety of Linux Container features on RHEL Server and RHEL Atomic Host systems by referring to the following documents to begin working with containers:

- Get Started with Docker Formatted Container Images: Steps you through the process of installing and using the docker command and related docker service to run, start, stop, build, and otherwise work directly with Docker-formatted container images.

- Getting Started with Kubernetes: Describes how to install and configure Kubernetes to manage and run container pods on a single system. This Kubernetes all-in-one setup is appropriate for trying out Kubernetes, but is not meant to be used as a production setup. Other Kubernetes topics in this guide include provisioning storage, troubleshooting, migrating from earlier versions, and understanding Kubernetes configuration files.

- Managing Containers: Covers a variety of container-related technologies on Red Hat systems. These topics include configuring storage for the docker service, signing images, using systemd with containers (to either start containers or start services inside of containers), running super pri vileged containers and system containers, and running containers without the docker service (using skopeo and runc).

When you are ready for a full-blown Linux Container experience, refer to documentation associated with the following technologies:

- OpenShift Container Platform: Provides a complete container development and deployment environment.

- Atomic Host Installation and Configuration: Provides information on setting up and managing RHEL Atomic Host systems for deploying containers.

1.2. Linux Containers Architecture

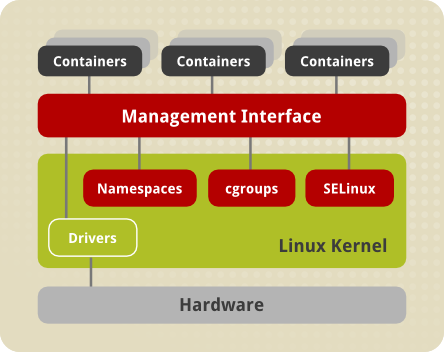

Several components are needed for Linux Containers to function correctly, most of them are provided by the Linux kernel. Kernel namespaces ensure process isolation and cgroups are employed to control the system resources. SELinux is used to assure separation between the host and the container and also between the individual containers. Management interface forms a higher layer that interacts with the aforementioned kernel components and provides tools for construction and management of containers.

The following scheme illustrates the architecture of Linux Containers in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7:

Namespaces

The kernel provides process isolation by creating separate namespaces for containers. Namespaces enable creating an abstraction of a particular global system resource and make it appear as a separated instance to processes within a namespace. Consequently, several containers can use the same resource simultaneously without creating a conflict. There are several types of namespaces:

-

Mount namespaces isolate the set of file system mount points seen by a group of processes so that processes in different mount namespaces can have different views of the file system hierarchy. With mount namespaces, the mount() and umount() system calls cease to operate on a global set of mount points (visible to all processes) and instead perform operations that affect just the mount namespace associated with the container process. For example, each container can have its own

/tmpor/vardirectory or even have an entirely different userspace. -

UTS namespaces isolate two system identifiers – nodename and domainname, returned by the uname() system call. This allows each container to have its own hostname and NIS domain name, which is useful for initialization and configuration scripts based on these names. You can test this isolation by executing the

hostnamecommand on the host system and a container – the results will differ. - IPC namespaces isolate certain interprocess communication (IPC) resources, such as System V IPC objects and POSIX message queues. This means that two containers can create shared memory segments and semaphores with the same name, but are not able to interact with other containers memory segments or shared memory.

-

PID namespaces allow processes in different containers to have the same PID, so each container can have its own init (PID1) process that manages various system initialization tasks as well as containers life cycle. Also, each container has its unique

/procdirectory. Note that from within the container you can monitor only processes running inside this container. In other words, the container is only aware of its native processes and can not "see" the processes running in different parts of the system. On the other hand, the host operating system is aware of processes running inside of the container, but assigns them different PID numbers. For example, run theps -eZ | grep systemd$command on host to see all instances of systemd including those running inside of containers. -

Network namespaces provide isolation of network controllers, system resources associated with networking, firewall and routing tables. This allows container to use separate virtual network stack, loopback device and process space. You can add virtual or real devices to the container, assign them their own IP Addresses and even full iptables rules. You can view the different network settings by executing the

ip addrcommand on the host and inside the container.

Note

There is another type of namespace called user namespace. User namespaces are similar to PID namespaces, they allow you to specify a range of host UIDs dedicated to the container. Consequently, a process can have full root privileges for operations inside the container, and at the same time be unprivileged for operations outside the container. For compatibility reasons, user namespaces are turned off in the current version of Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7, but will be enabled in the near future.

Control Groups (cgroups)

The kernel uses cgroups to group processes for the purpose of system resource management. Cgroups allocate CPU time, system memory, network bandwidth, or combinations of these among user-defined groups of tasks. In Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7, cgroups are managed with systemd slice, scope, and service units. For more information on cgroups, see the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Resource Management Guide.

SELinux

SELinux provides secure separation of containers by applying SELinux policy and labels. It integrates with virtual devices by using the sVirt technology. For more information see the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 SELinux Users and Administrators Guide.

Management Interface

1.3. Secure Containers with SELinux

From the security point of view, there is a need to isolate the host system from a container and to isolate containers from each other. The kernel features used by containers, namely cgroups and namespaces, by themselves provide a certain level of security. Cgroups ensure that a single container cannot exhaust a large amount of system resources, thus preventing some denial-of-service attacks. By virtue of namespaces, the /dev directory created within a container is private to each container, and therefore unaffected by the host changes. However, this can not prevent a hostile process from breaking out of the container since the entire system is not namespaced or containerized. Another level of separation, provided by SELinux, is therefore needed.

Security-Enhanced Linux (SELinux) is an implementation of a mandatory access control (MAC) mechanism, multi-level security (MLS), and multi-category security (MCS) in the Linux kernel. The sVirt project builds upon SELinux and integrates with Libvirt to provide a MAC framework for virtual machines and containers. This architecture provides a secure separation for containers as it prevents root processes within the container from interfering with other processes running outside this container. The containers created with Docker are automatically assigned with an SELinux context specified in the SELinux policy.

By default, containers created with libvirt tools are assigned with the virtd_lxc_t label (execute ps -eZ | grep virtd_lxc_t). You can apply sVirt by setting static or dynamic labeling for processes inside the container.

Note

You might notice that SELinux appears to be disabled inside the container even though it is running in enforcing mode on host system – you can verify this by executing the getenforce command on host and in the container. This is to prevent utilities that have SELinux awareness, such as setenforce, to perform any SELinux activity inside the container.

Note that if SELinux is disabled or running in permissive mode on the host machine, containers are not separated securely enough. For more information about SELinux, refer to Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 SELinux Users and Administrators Guide, sVirt is described in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Virtualization Security Guide.

Note

Note that currently it is not possible to run containers with SELinux enabled on the B-tree file system (Btrfs). Therefore, to use Docker with SELinux enabled, which is highly recommended, make sure the /var/lib/docker is not placed on Btrfs. In case you need to run Docker on Btrfs, disable SElinux by removing the --selinux-enabled entry from the /lib/systemd/system/docker.service configuration file.

1.4. Container Use Cases

1.4.1. Image-based Containers

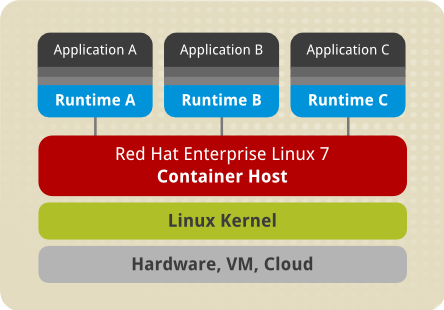

Image-based containers package applications with individual runtime stacks, making the resultant containers independent from the host operating system. This makes it possible to run several instances of an application, each developed for a different platform. This is possible because the container run time and the application run time are deployed in the form of an image. For example, Runtime A could refer to Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.5, Runtime B could refer to version 6.6 and so on.

Image-based containers allow you to host multiple instances and versions of an application, with minimal overhead and increased flexibility. Such containers are not tied to the host-specific configuration, which makes them portable.

Docker format relies on the device mapper thin provisioning technology that is an advanced variation of LVM snapshots to implement copy-on-write in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7.

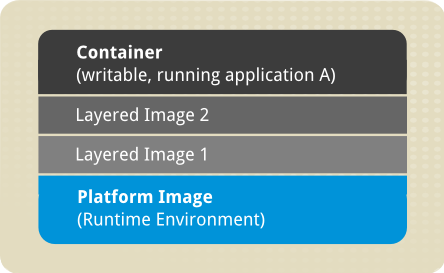

The above image shows the fundamental components of any image-based container:

-

Container – (in the narrow sense of the word) an active component in which an application runs. Each container is based on an image that holds necessary configuration data. When you launch a container from an image, a writable layer is added on top of this image. Every time you commit a container (using the

docker commitcommand), a new image layer is added to store your changes. - Image – a static snapshot of the containers' configuration. Image is a read-only layer that is never modified, all changes are made in top-most writable layer, and can be saved only by creating a new image. Each image depends on one or more parent images.

- Platform Image – an image that has no parent. Platform images define the runtime environment, packages and utilities necessary for a containerized application to run. The work with Docker usually starts by pulling the platform image. The platform image is read-only, so any changes are reflected in the copied images stacked on top of it. Red Hat provides a platform image for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 as well as Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.

The images piled on top of the platform image create an application layer that contains software dependencies for the containerized application. For example, the layered images in a given container could have added software dependencies required by the containerized application.

The whole container can be very large or it could be made really small depending on how many packages are included in the application layer. Further layering of the images is possible, such as software from 3rd party independent software vendors. From a user point of view there is still one container, but from an operational point of view there can be many layers behind it.

1.5. Linux Containers Compared to KVM Virtualization

KVM virtual machines require a kernel of their own. Linux containers share the kernel of the host operating system. It is usually possible to launch a much larger number of containers than virtual machines on the same hardware.

Both Linux Containers and KVM virtualization have certain advantages and drawbacks that influence the use cases in which these technologies are typically applied:

KVM virtualization:

- KVM virtualization enables booting full operating systems of different kinds, even non-Linux systems. The resource-hungry nature of virtual machines (as compared to containers) means that the number of virtual machines that can be run on a host is lower than the number of containers that can be run on the same host.

- Running separate kernel instances generally provides separation and security. The unexpected termination of one of the kernels does not disable the whole system.

- Guest virtual machine is isolated from host changes, which allows to run different versions of the same application on the host and virtual machine. KVM also provides many useful features such as live migration. For more information on these capabilities, see Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Virtualization Deployment and Administration Guide.

Linux Containers:

- Linux Containers are designed to support isolation of one or more applications.

- System-wide changes are visible in each container. For example, if you upgrade an application on the host machine, this change will apply to all sandboxes that run instances of this application.

- Since containers are lightweight, a large number of them can run simultaneously on a host machine. The theoretical maximum is 6000 containers and 12,000 bind mounts of root file system directories.

1.6. Additional Resources

To learn more about general principles and architecture of Linux Containers, refer to the following resources.

Installed Documentation

-

docker(1) — The manual page of the

dockercommand.

Online Documentation

- Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Virtualization Deployment and Administration Guide — this topic instructs how to configure a Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 host physical machine and how to install and configure guest virtual machines with different distributions, using the KVM hypervisor. Also included PCI device configuration, SR-IOV, networking, storage, device and guest virtual machine management, as well as troubleshooting, compatibility and restrictions.

- Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 SELinux Users and Administrators Guide — The SELinux Users and Administrators Guide for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 documents the basics and principles upon which SELinux functions, as well as practical tasks to set up and configure various services.

- Get Started with Docker Formatted Container Images on Red Hat Systems — This quick start guide describes the essential Docker-related tasks along with a number of examples.

- Documentation on the Docker Project Site — The official documentation of the Docker project.