Red Hat Training

A Red Hat training course is available for RHEL 8

Managing, monitoring, and updating the kernel

A guide to managing the Linux kernel on Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8

Abstract

Making open source more inclusive

Red Hat is committed to replacing problematic language in our code, documentation, and web properties. We are beginning with these four terms: master, slave, blacklist, and whitelist. Because of the enormity of this endeavor, these changes will be implemented gradually over several upcoming releases. For more details, see our CTO Chris Wright’s message.

Providing feedback on Red Hat documentation

We appreciate your feedback on our documentation. Let us know how we can improve it.

Submitting feedback through Jira (account required)

- Log in to the Jira website.

- Click Create in the top navigation bar.

- Enter a descriptive title in the Summary field.

- Enter your suggestion for improvement in the Description field. Include links to the relevant parts of the documentation.

- Click Create at the bottom of the dialogue.

Chapter 1. The Linux kernel

Learn about the Linux kernel and the Linux kernel RPM package provided and maintained by Red Hat (Red Hat kernel). Keep the Red Hat kernel updated, which ensures the operating system has all the latest bug fixes, performance enhancements, and patches, and is compatible with new hardware.

1.1. What the kernel is

The kernel is a core part of a Linux operating system that manages the system resources and provides interface between hardware and software applications.

The Red Hat kernel is a custom-built kernel based on the upstream Linux mainline kernel that Red Hat engineers further develop and harden with a focus on stability and compatibility with the latest technologies and hardware.

Before Red Hat releases a new kernel version, the kernel needs to pass a set of rigorous quality assurance tests.

The Red Hat kernels are packaged in the RPM format so that they are easily upgraded and verified by the YUM package manager.

Kernels that have not been compiled by Red Hat are not supported by Red Hat.

1.2. RPM packages

An RPM package consists of an archive of files and metadata used to install and erase these files. Specifically, the RPM package contains the following parts:

- GPG signature

- The GPG signature is used to verify the integrity of the package.

- Header (package metadata)

- The RPM package manager uses this metadata to determine package dependencies, where to install files, and other information.

- Payload

-

The payload is a

cpioarchive that contains files to install to the system.

There are two types of RPM packages. Both types share the file format and tooling, but have different contents and serve different purposes:

- Source RPM (SRPM)

- An SRPM contains source code and a SPEC file, which describes how to build the source code into a binary RPM. Optionally, the SRPM can contain patches to source code.

- Binary RPM

- A binary RPM contains the binaries built from the sources and patches.

1.3. The Linux kernel RPM package overview

The kernel RPM is a meta package that does not contain any files, but rather ensures that the following required sub-packages are properly installed:

kernel-core-

Contains the binary image of the kernel, all

initramfs-related objects to bootstrap the system, and a minimal number of kernel modules to ensure core functionality. This sub-package alone could be used in virtualized and cloud environments to provide a Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8 kernel with a quick boot time and a small disk size footprint. kernel-modules-

Contains the remaining kernel modules that are not present in

kernel-core.

The small set of kernel sub-packages above aims to provide a reduced maintenance surface to system administrators especially in virtualized and cloud environments.

Optional kernel packages are for example:

kernel-modules-extra- Contains kernel modules for rare hardware and modules which loading is disabled by default.

kernel-debug- Contains a kernel with numerous debugging options enabled for kernel diagnosis, at the expense of reduced performance.

kernel-tools- Contains tools for manipulating the Linux kernel and supporting documentation.

kernel-devel-

Contains the kernel headers and makefiles sufficient to build modules against the

kernelpackage. kernel-abi-stablelists-

Contains information pertaining to the RHEL kernel ABI, including a list of kernel symbols that are needed by external Linux kernel modules and a

yumplug-in to aid enforcement. kernel-headers- Includes the C header files that specify the interface between the Linux kernel and user-space libraries and programs. The header files define structures and constants that are needed for building most standard programs.

Additional resources

1.4. Displaying contents of a kernel package

To determine if a kernel package provides a specific file, such as a module, you can display the file list of the package for your architecture by querying the repository. It is not necessary to download or install the package to display the file list.

Use the dnf utility to query the file list, for example, of the kernel-core, kernel-modules-core, or kernel-modules package. Note that the kernel package is a meta package that does not contain any files.

Procedure

List the available versions of a package:

$ yum repoquery <package_name>For example, list the available versions of the

kernel-corepackage:$ yum repoquery kernel-core kernel-core-0:4.18.0-147.0.2.el8_1.x86_64 kernel-core-0:4.18.0-147.0.3.el8_1.x86_64 kernel-core-0:4.18.0-147.3.1.el8_1.x86_64 kernel-core-0:4.18.0-147.5.1.el8_1.x86_64 kernel-core-0:4.18.0-147.8.1.el8_1.x86_64 kernel-core-0:4.18.0-147.el8.x86_64 …Display the list of files in a package:

$ yum repoquery -l <package_name>For example, display the list of files in the

kernel-core-0:5.14.0-162.23.1.el9_1.x86_64package.$ yum repoquery -l kernel-core-0:4.18.0-147.8.1.el8_1.x86_64 /boot/.vmlinuz-4.18.0-147.8.1.el8_1.x86_64.hmac /boot/System.map-4.18.0-147.8.1.el8_1.x86_64 /boot/config-4.18.0-147.8.1.el8_1.x86_64 /boot/initramfs-4.18.0-147.8.1.el8_1.x86_64.img /boot/symvers-4.18.0-147.8.1.el8_1.x86_64.gz /boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-147.8.1.el8_1.x86_64 /etc/ld.so.conf.d/kernel-4.18.0-147.8.1.el8_1.x86_64.conf /lib/modules /lib/modules/4.18.0-147.8.1.el8_1.x86_64 ...

Additional resources

1.5. Installing specific kernel versions

Install new kernels using the yum package manager.

Procedure

To install a specific kernel version, enter the following command:

# yum install kernel-{version}

Additional resources

1.6. Updating the kernel

Update the kernel using the yum package manager.

Procedure

To update the kernel, enter the following command:

# yum update kernelThis command updates the kernel along with all dependencies to the latest available version.

- Reboot your system for the changes to take effect.

When upgrading from RHEL 7 to RHEL 8, follow relevant sections of the Upgrading from RHEL 7 to RHEL 8 document.

Additional resources

1.7. Setting a kernel as default

Set a specific kernel as default using the grubby command-line tool and GRUB.

Procedure

Setting the kernel as default, using the

grubbytoolEnter the following command to set the kernel as default using the

grubbytool:# grubby --set-default $kernel_pathThe command uses a machine ID without the

.confsuffix as an argument.NoteThe machine ID is located in the

/boot/loader/entries/directory.

Setting the kernel as default, using the

idargumentList the boot entries using the

idargument and then set an intended kernel as default:# grubby --info ALL | grep id # grubby --set-default /boot/vmlinuz-<version>.<architecture>

NoteTo list the boot entries using the

titleargument, execute the# grubby --info=ALL | grep titlecommand.

Setting the default kernel for only the next boot

Execute the following command to set the default kernel for only the next reboot using the

grub2-rebootcommand:# grub2-reboot <index|title|id>WarningSet the default kernel for only the next boot with care. Installing new kernel RPM’s, self-built kernels, and manually adding the entries to the

/boot/loader/entries/directory may change the index values.

Chapter 2. Managing kernel modules

Learn about kernel modules, how to display their information, and how to perform basic administrative tasks with kernel modules.

2.1. Introduction to kernel modules

The Red Hat Enterprise Linux kernel can be extended with optional, additional pieces of functionality, called kernel modules, without having to reboot the system. On RHEL 8, kernel modules are extra kernel code which is built into compressed <KERNEL_MODULE_NAME>.ko.xz object files.

The most common functionality enabled by kernel modules are:

- Device driver which adds support for new hardware

- Support for a file system such as GFS2 or NFS

- System calls

On modern systems, kernel modules are automatically loaded when needed. However, in some cases it is necessary to load or unload modules manually.

Like the kernel itself, the modules can take parameters that customize their behavior if needed.

Tooling is provided to inspect which modules are currently running, which modules are available to load into the kernel and which parameters a module accepts. The tooling also provides a mechanism to load and unload kernel modules into the running kernel.

2.2. Kernel module dependencies

Certain kernel modules sometimes depend on one or more other kernel modules. The /lib/modules/<KERNEL_VERSION>/modules.dep file contains a complete list of kernel module dependencies for the respective kernel version.

depmod

The dependency file is generated by the depmod program, which is a part of the kmod package. Many of the utilities provided by kmod take module dependencies into account when performing operations so that manual dependency-tracking is rarely necessary.

The code of kernel modules is executed in kernel-space in the unrestricted mode. Because of this, you should be mindful of what modules you are loading.

weak-modules

In addition to depmod, Red Hat Enterprise Linux provides the weak-modules script shipped also with the kmod package. weak-modules determines which modules are kABI-compatible with installed kernels. While checking modules kernel compatibility, weak-modules processes modules symbol dependencies from higher to lower release of kernel for which they were built. This means that weak-modules processes each module independently of kernel release they were built against.

Additional resources

-

The

modules.dep(5)manual page -

The

depmod(8)manual page - What is the purpose of weak-modules script shipped with Red Hat Enterprise Linux?

- What is Kernel Application Binary Interface (kABI)?

2.3. Listing installed kernel modules

The grubby --info=ALL command displays an indexed list of installed kernels on !BLS and BLS installs.

Procedure

List the installed kernels using the following command:

# grubby --info=ALL | grep titleThe list of all installed kernels is displayed as follows:

title=Red Hat Enterprise Linux (4.18.0-20.el8.x86_64) 8.0 (Ootpa) title=Red Hat Enterprise Linux (4.18.0-19.el8.x86_64) 8.0 (Ootpa) title=Red Hat Enterprise Linux (4.18.0-12.el8.x86_64) 8.0 (Ootpa) title=Red Hat Enterprise Linux (4.18.0) 8.0 (Ootpa) title=Red Hat Enterprise Linux (0-rescue-2fb13ddde2e24fde9e6a246a942caed1) 8.0 (Ootpa)

The above example displays the installed kernels list of grubby-8.40-17, from the GRUB menu.

2.4. Listing currently loaded kernel modules

View the currently loaded kernel modules.

Prerequisites

-

The

kmodpackage is installed.

Procedure

To list all currently loaded kernel modules, enter:

$ lsmod Module Size Used by fuse 126976 3 uinput 20480 1 xt_CHECKSUM 16384 1 ipt_MASQUERADE 16384 1 xt_conntrack 16384 1 ipt_REJECT 16384 1 nft_counter 16384 16 nf_nat_tftp 16384 0 nf_conntrack_tftp 16384 1 nf_nat_tftp tun 49152 1 bridge 192512 0 stp 16384 1 bridge llc 16384 2 bridge,stp nf_tables_set 32768 5 nft_fib_inet 16384 1 …In the example above:

-

The

Modulecolumn provides the names of currently loaded modules. -

The

Sizecolumn displays the amount of memory per module in kilobytes. -

The

Used bycolumn shows the number, and optionally the names of modules that are dependent on a particular module.

-

The

Additional resources

-

The

/usr/share/doc/kmod/READMEfile -

The

lsmod(8)manual page

2.5. Listing all installed kernels

Use the grubby utility to list all installed kernels on your system.

Prerequisites

- You have root permissions.

Procedure

To list all installed kernels, enter:

# grubby --info=ALL | grep ^kernel kernel="/boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-305.10.2.el8_4.x86_64" kernel="/boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-240.el8.x86_64" kernel="/boot/vmlinuz-0-rescue-41eb2e172d7244698abda79a51778f1b"

The output displays path to all the installed kernels, and displays also their respective versions.

2.6. Displaying information about kernel modules

Use the modinfo command to display some detailed information about the specified kernel module.

Prerequisites

-

The

kmodpackage is installed.

Procedure

To display information about any kernel module, enter:

$ modinfo <KERNEL_MODULE_NAME>For example:

$ modinfo virtio_net filename: /lib/modules/4.18.0-94.el8.x86_64/kernel/drivers/net/virtio_net.ko.xz license: GPL description: Virtio network driver rhelversion: 8.1 srcversion: 2E9345B281A898A91319773 alias: virtio:d00000001v* depends: net_failover intree: Y name: virtio_net vermagic: 4.18.0-94.el8.x86_64 SMP mod_unload modversions … parm: napi_weight:int parm: csum:bool parm: gso:bool parm: napi_tx:boolYou can query information about all available modules, regardless of whether they are loaded or not. The

parmentries show parameters the user is able to set for the module, and what type of value they expect.NoteWhen entering the name of a kernel module, do not append the

.ko.xzextension to the end of the name. Kernel module names do not have extensions; their corresponding files do.

Additional resources

-

The

modinfo(8)manual page

2.7. Loading kernel modules at system runtime

The optimal way to expand the functionality of the Linux kernel is by loading kernel modules. Use the modprobe command to find and load a kernel module into the currently running kernel.

The changes described in this procedure will not persist after rebooting the system. For information about how to load kernel modules to persist across system reboots, see Loading kernel modules automatically at system boot time.

Prerequisites

- Root permissions

-

The

kmodpackage is installed. - The respective kernel module is not loaded. To ensure this is the case, list the loaded kernel modules.

Procedure

Select a kernel module you want to load.

The modules are located in the

/lib/modules/$(uname -r)/kernel/<SUBSYSTEM>/directory.Load the relevant kernel module:

# modprobe <MODULE_NAME>NoteWhen entering the name of a kernel module, do not append the

.ko.xzextension to the end of the name. Kernel module names do not have extensions; their corresponding files do.

Verification

Optionally, verify the relevant module was loaded:

$ lsmod | grep <MODULE_NAME>If the module was loaded correctly, this command displays the relevant kernel module. For example:

$ lsmod | grep serio_raw serio_raw 16384 0

Additional resources

-

The

modprobe(8)manual page

2.8. Unloading kernel modules at system runtime

At times, you find that you need to unload certain kernel modules from the running kernel. Use the modprobe command to find and unload a kernel module at system runtime from the currently loaded kernel.

Do not unload kernel modules when they are used by the running system. Doing so can lead to an unstable or non-operational system.

After finishing this procedure, the kernel modules that are defined to be automatically loaded on boot, will not stay unloaded after rebooting the system. For information about how to counter this outcome, see Preventing kernel modules from being automatically loaded at system boot time.

Prerequisites

- Root permissions

-

The

kmodpackage is installed.

Procedure

List all loaded kernel modules:

# lsmodSelect the kernel module you want to unload.

If a kernel module has dependencies, unload those prior to unloading the kernel module. For details on identifying modules with dependencies, see Listing currently loaded kernel modules and Kernel module dependencies.

Unload the relevant kernel module:

# modprobe -r <MODULE_NAME>When entering the name of a kernel module, do not append the

.ko.xzextension to the end of the name. Kernel module names do not have extensions; their corresponding files do.

Verification

Optionally, verify the relevant module was unloaded:

$ lsmod | grep <MODULE_NAME>If the module was unloaded successfully, this command does not display any output.

Additional resources

-

modprobe(8)manual page

2.9. Unloading kernel modules at early stages of the boot process

In certain situations, it is necessary to unload a kernel module very early in the booting process. For example, when the kernel module contains a code, which causes the system to become unresponsive, and the user is not able to reach the stage to permanently disable the rogue kernel module. In that case it is possible to temporarily block the loading of the kernel module using a boot loader.

You can edit the relevant boot loader entry to unload the desired kernel module before the booting sequence continues.

The changes described in this procedure will not persist after the next reboot. For information about how to add a kernel module to a denylist so that it will not be automatically loaded during the boot process, see Preventing kernel modules from being automatically loaded at system boot time.

Prerequisites

- You have a loadable kernel module that you want to prevent from loading for some reason.

Procedure

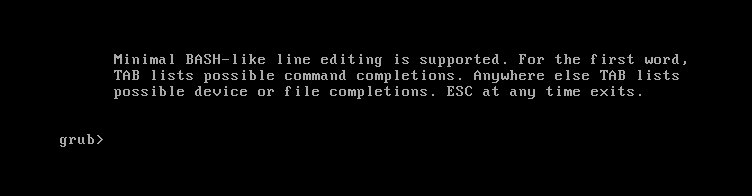

- Boot the system into the boot loader.

- Use the cursor keys to highlight the relevant boot loader entry.

Press the e key to edit the entry.

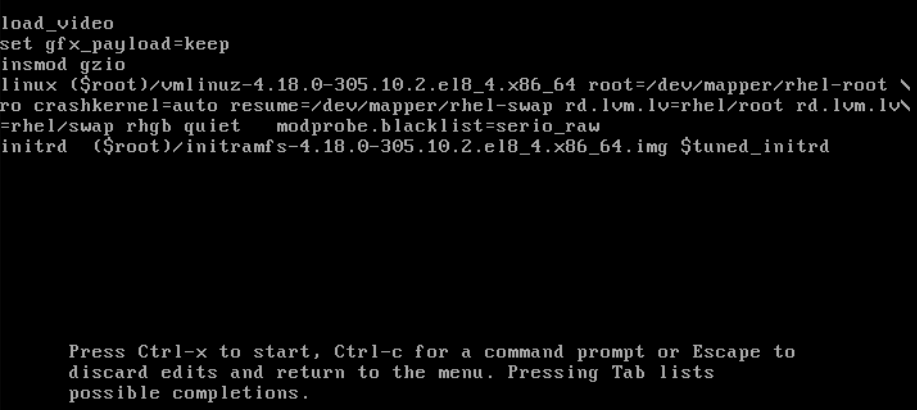

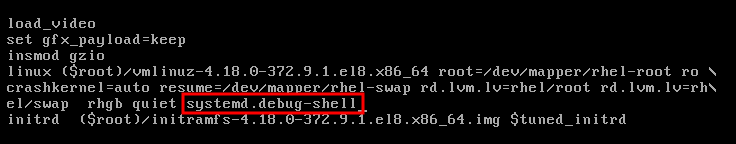

Figure 2.1. Kernel boot menu

- Use the cursor keys to navigate to the line that starts with linux.

Append

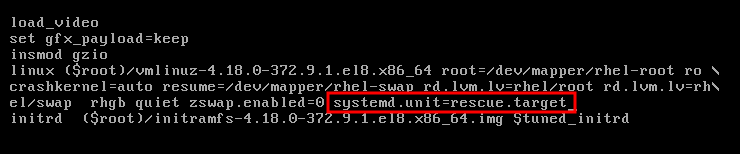

modprobe.blacklist=module_nameto the end of the line.Figure 2.2. Kernel boot entry

The

serio_rawkernel module illustrates a rogue module to be unloaded early in the boot process.- Press Ctrl+X to boot using the modified configuration.

Verification

Once the system fully boots, verify that the relevant kernel module is not loaded.

# lsmod | grep serio_raw

Additional resources

2.10. Loading kernel modules automatically at system boot time

Configure a kernel module so that it is loaded automatically during the boot process.

Prerequisites

- Root permissions

-

The

kmodpackage is installed.

Procedure

Select a kernel module you want to load during the boot process.

The modules are located in the

/lib/modules/$(uname -r)/kernel/<SUBSYSTEM>/directory.Create a configuration file for the module:

# echo <MODULE_NAME> > /etc/modules-load.d/<MODULE_NAME>.confNoteWhen entering the name of a kernel module, do not append the

.ko.xzextension to the end of the name. Kernel module names do not have extensions; their corresponding files do.Optionally, after reboot, verify the relevant module was loaded:

$ lsmod | grep <MODULE_NAME>The example command above should succeed and display the relevant kernel module.

The changes described in this procedure will persist after rebooting the system.

Additional resources

-

modules-load.d(5)manual page

2.11. Preventing kernel modules from being automatically loaded at system boot time

You can prevent the system from loading a kernel module automatically during the boot process by listing the module in modprobe configuration file with a corresponding command.

Prerequisites

-

The commands in this procedure require root privileges. Either use

su -to switch to the root user or preface the commands withsudo. -

The

kmodpackage is installed. - Ensure that your current system configuration does not require a kernel module you plan to deny.

Procedure

List modules loaded to the currently running kernel by using the

lsmodcommand:$ lsmod Module Size Used by tls 131072 0 uinput 20480 1 snd_seq_dummy 16384 0 snd_hrtimer 16384 1 …In the output, identify the module you want to prevent from being loaded.

Alternatively, identify an unloaded kernel module you want to prevent from potentially loading in the

/lib/modules/<KERNEL-VERSION>/kernel/<SUBSYSTEM>/directory, for example:$ ls /lib/modules/4.18.0-477.20.1.el8_8.x86_64/kernel/crypto/ ansi_cprng.ko.xz chacha20poly1305.ko.xz md4.ko.xz serpent_generic.ko.xz anubis.ko.xz cmac.ko.xz…

Create a configuration file serving as a denylist:

# touch /etc/modprobe.d/denylist.confIn a text editor of your choice, combine the names of modules you want to exclude from automatic loading to the kernel with the

blacklistconfiguration command, for example:# Prevents <KERNEL-MODULE-1> from being loaded blacklist <MODULE-NAME-1> install <MODULE-NAME-1> /bin/false # Prevents <KERNEL-MODULE-2> from being loaded blacklist <MODULE-NAME-2> install <MODULE-NAME-2> /bin/false …

Because the

blacklistcommand does not prevent the module from being loaded as a dependency for another kernel module that is not in a denylist, you must also define theinstallline. In this case, the system runs/bin/falseinstead of installing the module. The lines starting with a hash sign are comments you can use to make the file more readable.NoteWhen entering the name of a kernel module, do not append the

.ko.xzextension to the end of the name. Kernel module names do not have extensions; their corresponding files do.Create a backup copy of the current initial RAM disk image before rebuilding:

# cp /boot/initramfs-$(uname -r).img /boot/initramfs-$(uname -r).bak.$(date +%m-%d-%H%M%S).imgAlternatively, create a backup copy of an initial RAM disk image which corresponds to the kernel version for which you want to prevent kernel modules from automatic loading:

# cp /boot/initramfs-<VERSION>.img /boot/initramfs-<VERSION>.img.bak.$(date +%m-%d-%H%M%S)

Generate a new initial RAM disk image to apply the changes:

# dracut -f -vIf you build an initial RAM disk image for a different kernel version than your system currently uses, specify both target

initramfsand kernel version:# dracut -f -v /boot/initramfs-<TARGET-VERSION>.img <CORRESPONDING-TARGET-KERNEL-VERSION>

Restart the system:

$ reboot

The changes described in this procedure will take effect and persist after rebooting the system. If you incorrectly list a key kernel module in the denylist, you can switch the system to an unstable or non-operational state.

Additional resources

- How do I prevent a kernel module from loading automatically? solution article

-

modprobe.d(5)anddracut(8)man pages

2.12. Compiling custom kernel modules

You can build a sampling kernel module as requested by various configurations at hardware and software level.

Prerequisites

You installed the

kernel-devel,gcc, andelfutils-libelf-develpackages.# dnf install kernel-devel-$(uname -r) gcc elfutils-libelf-devel

- You have root permissions.

-

You created the

/root/testmodule/directory where you compile the custom kernel module.

Procedure

Create the

/root/testmodule/test.cfile with the following content.#include <linux/module.h> #include <linux/kernel.h> int init_module(void) { printk("Hello World\n This is a test\n"); return 0; } void cleanup_module(void) { printk("Good Bye World"); }The

test.cfile is a source file that provides the main functionality to the kernel module. The file has been created in a dedicated/root/testmodule/directory for organizational purposes. After the module compilation, the/root/testmodule/directory will contain multiple files.The

test.cfile includes from the system libraries:-

The

linux/kernel.hheader file is necessary for theprintk()function in the example code. -

The

linux/module.hfile contains function declarations and macro definitions to be shared between several source files written in C programming language.

-

The

-

Follow the

init_module()andcleanup_module()functions to start and end the kernel logging functionprintk(), which prints text. Create the

/root/testmodule/Makefilefile with the following content.obj-m := test.o

The Makefile contains instructions that the compiler has to produce an object file specifically named

test.o. Theobj-mdirective specifies that the resultingtest.kofile is going to be compiled as a loadable kernel module. Alternatively, theobj-ydirective would instruct to buildtest.koas a built-in kernel module.Compile the kernel module.

# make -C /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/build M=/root/testmodule modules make: Entering directory '/usr/src/kernels/4.18.0-305.el8.x86_64' CC [M] /root/testmodule/test.o Building modules, stage 2. MODPOST 1 modules WARNING: modpost: missing MODULE_LICENSE() in /root/testmodule/test.o see include/linux/module.h for more information CC /root/testmodule/test.mod.o LD [M] /root/testmodule/test.ko make: Leaving directory '/usr/src/kernels/4.18.0-305.el8.x86_64'The compiler creates an object file (

test.o) for each source file (test.c) as an intermediate step before linking them together into the final kernel module (test.ko).After a successful compilation,

/root/testmodule/contains additional files that relate to the compiled custom kernel module. The compiled module itself is represented by thetest.kofile.

Verification

Optional: check the contents of the

/root/testmodule/directory:# ls -l /root/testmodule/ total 152 -rw-r—r--. 1 root root 16 Jul 26 08:19 Makefile -rw-r—r--. 1 root root 25 Jul 26 08:20 modules.order -rw-r—r--. 1 root root 0 Jul 26 08:20 Module.symvers -rw-r—r--. 1 root root 224 Jul 26 08:18 test.c -rw-r—r--. 1 root root 62176 Jul 26 08:20 test.ko -rw-r—r--. 1 root root 25 Jul 26 08:20 test.mod -rw-r—r--. 1 root root 849 Jul 26 08:20 test.mod.c -rw-r—r--. 1 root root 50936 Jul 26 08:20 test.mod.o -rw-r—r--. 1 root root 12912 Jul 26 08:20 test.oCopy the kernel module to the

/lib/modules/$(uname -r)/directory:# cp /root/testmodule/test.ko /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/Update the modular dependency list:

# depmod -aLoad the kernel module:

# modprobe -v test insmod /lib/modules/4.18.0-305.el8.x86_64/test.ko

Verify that the kernel module was successfully loaded:

# lsmod | grep test test 16384 0Read the latest messages from the kernel ring buffer:

# dmesg [74422.545004] Hello World This is a test

Additional resources

Chapter 3. Signing a kernel and modules for Secure Boot

You can enhance the security of your system by using a signed kernel and signed kernel modules. On UEFI-based build systems where Secure Boot is enabled, you can self-sign a privately built kernel or kernel modules. Furthermore, you can import your public key into a target system where you want to deploy your kernel or kernel modules.

If Secure Boot is enabled, all of the following components have to be signed with a private key and authenticated with the corresponding public key:

- UEFI operating system boot loader

- The Red Hat Enterprise Linux kernel

- All kernel modules

If any of these components are not signed and authenticated, the system cannot finish the booting process.

RHEL 8 includes:

- Signed boot loaders

- Signed kernels

- Signed kernel modules

In addition, the signed first-stage boot loader and the signed kernel include embedded Red Hat public keys. These signed executable binaries and embedded keys enable RHEL 8 to install, boot, and run with the Microsoft UEFI Secure Boot Certification Authority keys that are provided by the UEFI firmware on systems that support UEFI Secure Boot.

- Not all UEFI-based systems include support for Secure Boot.

- The build system, where you build and sign your kernel module, does not need to have UEFI Secure Boot enabled and does not even need to be a UEFI-based system.

3.1. Prerequisites

To be able to sign externally built kernel modules, install the utilities from the following packages:

# yum install pesign openssl kernel-devel mokutil keyutilsTable 3.1. Required utilities

Utility Provided by package Used on Purpose efikeygenpesignBuild system

Generates public and private X.509 key pair

opensslopensslBuild system

Exports the unencrypted private key

sign-filekernel-develBuild system

Executable file used to sign a kernel module with the private key

mokutilmokutilTarget system

Optional utility used to manually enroll the public key

keyctlkeyutilsTarget system

Optional utility used to display public keys in the system keyring

3.2. What is UEFI Secure Boot

With the Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) Secure Boot technology, you can prevent the execution of the kernel-space code that has not been signed by a trusted key. The system boot loader is signed with a cryptographic key. The database of public keys, which is contained in the firmware, authorizes the signing key. You can subsequently verify a signature in the next-stage boot loader and the kernel.

UEFI Secure Boot establishes a chain of trust from the firmware to the signed drivers and kernel modules as follows:

-

An UEFI private key signs, and a public key authenticates the

shimfirst-stage boot loader. A certificate authority (CA) in turn signs the public key. The CA is stored in the firmware database. -

The

shimfile contains the Red Hat public key Red Hat Secure Boot (CA key 1) to authenticate the GRUB boot loader and the kernel. - The kernel in turn contains public keys to authenticate drivers and modules.

Secure Boot is the boot path validation component of the UEFI specification. The specification defines:

- Programming interface for cryptographically protected UEFI variables in non-volatile storage.

- Storing the trusted X.509 root certificates in UEFI variables.

- Validation of UEFI applications such as boot loaders and drivers.

- Procedures to revoke known-bad certificates and application hashes.

UEFI Secure Boot helps in the detection of unauthorized changes but does not:

- Prevent installation or removal of second-stage boot loaders.

- Require explicit user confirmation of such changes.

- Stop boot path manipulations. Signatures are verified during booting, not when the boot loader is installed or updated.

If the boot loader or the kernel are not signed by a system trusted key, Secure Boot prevents them from starting.

3.3. UEFI Secure Boot support

You can install and run RHEL 8 on systems with enabled UEFI Secure Boot if the kernel and all the loaded drivers are signed with a trusted key. Red Hat provides kernels and drivers that are signed and authenticated by the relevant Red Hat keys.

If you want to load externally built kernels or drivers, you must sign them as well.

Restrictions imposed by UEFI Secure Boot

- The system only runs the kernel-mode code after its signature has been properly authenticated.

- GRUB module loading is disabled because there is no infrastructure for signing and verification of GRUB modules. Allowing them to be loaded constitutes execution of untrusted code inside the security perimeter that Secure Boot defines.

- Red Hat provides a signed GRUB binary that contains all the supported modules on RHEL 8.

Additional resources

3.4. Requirements for authenticating kernel modules with X.509 keys

In RHEL 8, when a kernel module is loaded, the kernel checks the signature of the module against the public X.509 keys from the kernel system keyring (.builtin_trusted_keys) and the kernel platform keyring (.platform). The .platform keyring contains keys from third-party platform providers and custom public keys. The keys from the kernel system .blacklist keyring are excluded from verification.

You need to meet certain conditions to load kernel modules on systems with enabled UEFI Secure Boot functionality:

If UEFI Secure Boot is enabled or if the

module.sig_enforcekernel parameter has been specified:-

You can only load those signed kernel modules whose signatures were authenticated against keys from the system keyring (

.builtin_trusted_keys) and the platform keyring (.platform). -

The public key must not be on the system revoked keys keyring (

.blacklist).

-

You can only load those signed kernel modules whose signatures were authenticated against keys from the system keyring (

If UEFI Secure Boot is disabled and the

module.sig_enforcekernel parameter has not been specified:- You can load unsigned kernel modules and signed kernel modules without a public key.

If the system is not UEFI-based or if UEFI Secure Boot is disabled:

-

Only the keys embedded in the kernel are loaded onto

.builtin_trusted_keysand.platform. - You have no ability to augment that set of keys without rebuilding the kernel.

-

Only the keys embedded in the kernel are loaded onto

Table 3.2. Kernel module authentication requirements for loading

| Module signed | Public key found and signature valid | UEFI Secure Boot state | sig_enforce | Module load | Kernel tainted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsigned | - | Not enabled | Not enabled | Succeeds | Yes |

| Not enabled | Enabled | Fails | - | ||

| Enabled | - | Fails | - | ||

| Signed | No | Not enabled | Not enabled | Succeeds | Yes |

| Not enabled | Enabled | Fails | - | ||

| Enabled | - | Fails | - | ||

| Signed | Yes | Not enabled | Not enabled | Succeeds | No |

| Not enabled | Enabled | Succeeds | No | ||

| Enabled | - | Succeeds | No |

3.5. Sources for public keys

During boot, the kernel loads X.509 keys from a set of persistent key stores into the following keyrings:

-

The system keyring (

.builtin_trusted_keys) -

The

.platformkeyring -

The system

.blacklistkeyring

Table 3.3. Sources for system keyrings

| Source of X.509 keys | User can add keys | UEFI Secure Boot state | Keys loaded during boot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embedded in kernel | No | - |

|

|

UEFI | Limited | Not enabled | No |

| Enabled |

| ||

|

Embedded in the | No | Not enabled | No |

| Enabled |

| ||

| Machine Owner Key (MOK) list | Yes | Not enabled | No |

| Enabled |

|

.builtin_trusted_keys- A keyring that is built on boot

- Contains trusted public keys

-

rootprivileges are needed to view the keys

.platform- A keyring that is built on boot

- Contains keys from third-party platform providers and custom public keys

-

rootprivileges are needed to view the keys

.blacklist- A keyring with X.509 keys which have been revoked

-

A module signed by a key from

.blacklistwill fail authentication even if your public key is in.builtin_trusted_keys

- UEFI Secure Boot

db - A signature database

- Stores keys (hashes) of UEFI applications, UEFI drivers, and boot loaders

- The keys can be loaded on the machine

- UEFI Secure Boot

dbx - A revoked signature database

- Prevents keys from being loaded

-

The revoked keys from this database are added to the

.blacklistkeyring

3.6. Generating a public and private key pair

To use a custom kernel or custom kernel modules on a Secure Boot-enabled system, you must generate a public and private X.509 key pair. You can use the generated private key to sign the kernel or the kernel modules. You can also validate the signed kernel or kernel modules by adding the corresponding public key to the Machine Owner Key (MOK) for Secure Boot.

Apply strong security measures and access policies to guard the contents of your private key. In the wrong hands, the key could be used to compromise any system which is authenticated by the corresponding public key.

Procedure

Create an X.509 public and private key pair:

If you only want to sign custom kernel modules:

# efikeygen --dbdir /etc/pki/pesign \ --self-sign \ --module \ --common-name 'CN=Organization signing key' \ --nickname 'Custom Secure Boot key'

If you want to sign custom kernel:

# efikeygen --dbdir /etc/pki/pesign \ --self-sign \ --kernel \ --common-name 'CN=Organization signing key' \ --nickname 'Custom Secure Boot key'

When the RHEL system is running FIPS mode:

# efikeygen --dbdir /etc/pki/pesign \ --self-sign \ --kernel \ --common-name 'CN=Organization signing key' \ --nickname 'Custom Secure Boot key' --token 'NSS FIPS 140-2 Certificate DB'

NoteIn FIPS mode, you must use the

--tokenoption so thatefikeygenfinds the default "NSS Certificate DB" token in the PKI database.The public and private keys are now stored in the

/etc/pki/pesign/directory.

It is a good security practice to sign the kernel and the kernel modules within the validity period of its signing key. However, the sign-file utility does not warn you and the key will be usable in RHEL 8 regardless of the validity dates.

Additional resources

3.7. Example output of system keyrings

You can display information about the keys on the system keyrings using the keyctl utility from the keyutils package.

Prerequisites

- You have root permissions.

-

You have installed the

keyctlutility from thekeyutilspackage.

Example 3.1. Keyrings output

The following is a shortened example output of .builtin_trusted_keys, .platform, and .blacklist keyrings from a RHEL 8 system where UEFI Secure Boot is enabled.

# keyctl list %:.builtin_trusted_keys 6 keys in keyring: ...asymmetric: Red Hat Enterprise Linux Driver Update Program (key 3): bf57f3e87... ...asymmetric: Red Hat Secure Boot (CA key 1): 4016841644ce3a810408050766e8f8a29... ...asymmetric: Microsoft Corporation UEFI CA 2011: 13adbf4309bd82709c8cd54f316ed... ...asymmetric: Microsoft Windows Production PCA 2011: a92902398e16c49778cd90f99e... ...asymmetric: Red Hat Enterprise Linux kernel signing key: 4249689eefc77e95880b... ...asymmetric: Red Hat Enterprise Linux kpatch signing key: 4d38fd864ebe18c5f0b7... # keyctl list %:.platform 4 keys in keyring: ...asymmetric: VMware, Inc.: 4ad8da0472073... ...asymmetric: Red Hat Secure Boot CA 5: cc6fafe72... ...asymmetric: Microsoft Windows Production PCA 2011: a929f298e1... ...asymmetric: Microsoft Corporation UEFI CA 2011: 13adbf4e0bd82... # keyctl list %:.blacklist 4 keys in keyring: ...blacklist: bin:f5ff83a... ...blacklist: bin:0dfdbec... ...blacklist: bin:38f1d22... ...blacklist: bin:51f831f...

The .builtin_trusted_keys keyring in the example shows the addition of two keys from the UEFI Secure Boot db keys as well as the Red Hat Secure Boot (CA key 1), which is embedded in the shim boot loader.

Example 3.2. Kernel console output

The following example shows the kernel console output. The messages identify the keys with an UEFI Secure Boot related source. These include UEFI Secure Boot db, embedded shim, and MOK list.

# dmesg | egrep 'integrity.*cert'

[1.512966] integrity: Loading X.509 certificate: UEFI:db

[1.513027] integrity: Loaded X.509 cert 'Microsoft Windows Production PCA 2011: a929023...

[1.513028] integrity: Loading X.509 certificate: UEFI:db

[1.513057] integrity: Loaded X.509 cert 'Microsoft Corporation UEFI CA 2011: 13adbf4309...

[1.513298] integrity: Loading X.509 certificate: UEFI:MokListRT (MOKvar table)

[1.513549] integrity: Loaded X.509 cert 'Red Hat Secure Boot CA 5: cc6fa5e72868ba494e93...Additional resources

-

keyctl(1),dmesg(1)manual pages

3.8. Enrolling public key on target system by adding the public key to the MOK list

You must enroll your public key on all systems where you want to authenticate and load your kernel or kernel modules. You can import the public key on a target system in different ways so that the platform keyring (.platform) is able to use the public key to authenticate the kernel or kernel modules.

When RHEL 8 boots on a UEFI-based system with Secure Boot enabled, the kernel loads onto the platform keyring (.platform) all public keys that are in the Secure Boot db key database. At the same time, the kernel excludes the keys in the dbx database of revoked keys.

You can use the Machine Owner Key (MOK) facility feature to expand the UEFI Secure Boot key database. When RHEL 8 boots on an UEFI-enabled system with Secure Boot enabled, the keys on the MOK list are also added to the platform keyring (.platform) in addition to the keys from the key database. The MOK list keys are also stored persistently and securely in the same fashion as the Secure Boot database keys, but these are two separate facilities. The MOK facility is supported by shim, MokManager, GRUB, and the mokutil utility.

To facilitate authentication of your kernel module on your systems, consider requesting your system vendor to incorporate your public key into the UEFI Secure Boot key database in their factory firmware image.

Prerequisites

- You have generated a public and private key pair and know the validity dates of your public keys. For details, see Generating a public and private key pair.

Procedure

Export your public key to the

sb_cert.cerfile:# certutil -d /etc/pki/pesign \ -n 'Custom Secure Boot key' \ -Lr \ > sb_cert.cer

Import your public key into the MOK list:

# mokutil --import sb_cert.cer- Enter a new password for this MOK enrollment request.

Reboot the machine.

The

shimboot loader notices the pending MOK key enrollment request and it launchesMokManager.efito enable you to complete the enrollment from the UEFI console.Choose

Enroll MOK, enter the password you previously associated with this request when prompted, and confirm the enrollment.Your public key is added to the MOK list, which is persistent.

Once a key is on the MOK list, it will be automatically propagated to the

.platformkeyring on this and subsequent boots when UEFI Secure Boot is enabled.

3.9. Signing a kernel with the private key

You can obtain enhanced security benefits on your system by loading a signed kernel if the UEFI Secure Boot mechanism is enabled.

Prerequisites

- You have generated a public and private key pair and know the validity dates of your public keys. For details, see Generating a public and private key pair.

- You have enrolled your public key on the target system. For details, see Enrolling public key on target system by adding the public key to the MOK list.

- You have a kernel image in the ELF format available for signing.

Procedure

On the x64 architecture:

Create a signed image:

# pesign --certificate 'Custom Secure Boot key' \ --in vmlinuz-version \ --sign \ --out vmlinuz-version.signed

Replace

versionwith the version suffix of yourvmlinuzfile, andCustom Secure Boot keywith the name that you chose earlier.Optional: Check the signatures:

# pesign --show-signature \ --in vmlinuz-version.signed

Overwrite the unsigned image with the signed image:

# mv vmlinuz-version.signed vmlinuz-version

On the 64-bit ARM architecture:

Decompress the

vmlinuzfile:# zcat vmlinuz-version > vmlinux-versionCreate a signed image:

# pesign --certificate 'Custom Secure Boot key' \ --in vmlinux-version \ --sign \ --out vmlinux-version.signed

Optional: Check the signatures:

# pesign --show-signature \ --in vmlinux-version.signed

Compress the

vmlinuxfile:# gzip --to-stdout vmlinux-version.signed > vmlinuz-versionRemove the uncompressed

vmlinuxfile:# rm vmlinux-version*

3.10. Signing a GRUB build with the private key

On a system where the UEFI Secure Boot mechanism is enabled, you can sign a GRUB build with a custom existing private key. You must do this if you are using a custom GRUB build, or if you have removed the Microsoft trust anchor from your system.

Prerequisites

- You have generated a public and private key pair and know the validity dates of your public keys. For details, see Generating a public and private key pair.

- You have enrolled your public key on the target system. For details, see Enrolling public key on target system by adding the public key to the MOK list.

- You have a GRUB EFI binary available for signing.

Procedure

On the x64 architecture:

Create a signed GRUB EFI binary:

# pesign --in /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grubx64.efi \ --out /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grubx64.efi.signed \ --certificate 'Custom Secure Boot key' \ --sign

Replace

Custom Secure Boot keywith the name that you chose earlier.Optional: Check the signatures:

# pesign --in /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grubx64.efi.signed \ --show-signature

Overwrite the unsigned binary with the signed binary:

# mv /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grubx64.efi.signed \ /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grubx64.efi

On the 64-bit ARM architecture:

Create a signed GRUB EFI binary:

# pesign --in /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grubaa64.efi \ --out /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grubaa64.efi.signed \ --certificate 'Custom Secure Boot key' \ --sign

Replace

Custom Secure Boot keywith the name that you chose earlier.Optional: Check the signatures:

# pesign --in /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grubaa64.efi.signed \ --show-signature

Overwrite the unsigned binary with the signed binary:

# mv /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grubaa64.efi.signed \ /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grubaa64.efi

3.11. Signing kernel modules with the private key

You can enhance the security of your system by loading signed kernel modules if the UEFI Secure Boot mechanism is enabled.

Your signed kernel module is also loadable on systems where UEFI Secure Boot is disabled or on a non-UEFI system. As a result, you do not need to provide both a signed and unsigned version of your kernel module.

Prerequisites

- You have generated a public and private key pair and know the validity dates of your public keys. For details, see Generating a public and private key pair.

- You have enrolled your public key on the target system. For details, see Enrolling public key on target system by adding the public key to the MOK list.

- You have a kernel module in ELF image format available for signing.

Procedure

Export your public key to the

sb_cert.cerfile:# certutil -d /etc/pki/pesign \ -n 'Custom Secure Boot key' \ -Lr \ > sb_cert.cer

Extract the key from the NSS database as a PKCS #12 file:

# pk12util -o sb_cert.p12 \ -n 'Custom Secure Boot key' \ -d /etc/pki/pesign

- When the previous command prompts you, enter a new password that encrypts the private key.

Export the unencrypted private key:

# openssl pkcs12 \ -in sb_cert.p12 \ -out sb_cert.priv \ -nocerts \ -nodes

ImportantHandle the unencrypted private key with care.

Sign your kernel module. The following command appends the signature directly to the ELF image in your kernel module file:

# /usr/src/kernels/$(uname -r)/scripts/sign-file \ sha256 \ sb_cert.priv \ sb_cert.cer \ my_module.ko

Your kernel module is now ready for loading.

In RHEL 8, the validity dates of the key pair matter. The key does not expire, but the kernel module must be signed within the validity period of its signing key. The sign-file utility will not warn you of this. For example, a key that is only valid in 2019 can be used to authenticate a kernel module signed in 2019 with that key. However, users cannot use that key to sign a kernel module in 2020.

Verification

Display information about the kernel module’s signature:

# modinfo my_module.ko | grep signer signer: Your Name Key

Check that the signature lists your name as entered during generation.

NoteThe appended signature is not contained in an ELF image section and is not a formal part of the ELF image. Therefore, utilities such as

readelfcannot display the signature on your kernel module.Load the module:

# insmod my_module.koRemove (unload) the module:

# modprobe -r my_module.ko

Additional resources

3.12. Loading signed kernel modules

Once your public key is enrolled in the system keyring (.builtin_trusted_keys) and the MOK list, and after you have signed the respective kernel module with your private key, you can load your signed kernel module with the modprobe command.

Prerequisites

- You have generated the public and private key pair. For details, see Generating a public and private key pair.

- You have enrolled the public key into the system keyring. For details, see Enrolling public key on target system by adding the public key to the MOK list.

- You have signed a kernel module with the private key. For details, see Signing kernel modules with the private key.

Install the

kernel-modules-extrapackage, which creates the/lib/modules/$(uname -r)/extra/directory:# yum -y install kernel-modules-extra

Procedure

Verify that your public keys are on the system keyring:

# keyctl list %:.platformCopy the kernel module into the

extra/directory of the kernel that you want:# cp my_module.ko /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/extra/Update the modular dependency list:

# depmod -aLoad the kernel module:

# modprobe -v my_moduleOptionally, to load the module on boot, add it to the

/etc/modules-loaded.d/my_module.conffile:# echo "my_module" > /etc/modules-load.d/my_module.conf

Verification

Verify that the module was successfully loaded:

# lsmod | grep my_module

Additional resources

Chapter 4. Configuring kernel command-line parameters

With kernel command-line parameters, you can change the behavior of certain aspects of the Red Hat Enterprise Linux kernel at boot time. As a system administrator, you have full control over what options get set at boot. Certain kernel behaviors can only be set at boot time, so understanding how to make these changes is a key administration skill.

Changing the behavior of the system by modifying kernel command-line parameters may have negative effects on your system. Always test changes prior to deploying them in production. For further guidance, contact Red Hat Support.

4.1. What are kernel command-line parameters

With kernel command-line parameters, you can overwrite default values and set specific hardware settings. At boot time, you can configure the following features:

- The Red Hat Enterprise Linux kernel

- The initial RAM disk

- The user space features

By default, the kernel command-line parameters for systems using the GRUB boot loader are defined in the kernelopts variable of the /boot/grub2/grubenv file for each kernel boot entry.

For IBM Z, the kernel command-line parameters are stored in the boot entry configuration file because the zipl boot loader does not support environment variables. Thus, the kernelopts environment variable cannot be used.

You can manipulate boot loader configuration files by using the grubby utility. With grubby, you can perform these actions:

- Change the default boot entry.

- Add or remove arguments from a GRUB menu entry.

Additional resources

-

kernel-command-line(7),bootparam(7)anddracut.cmdline(7)manual pages - How to install and boot custom kernels in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8

-

The

grubby(8)manual page

4.2. Understanding boot entries

A boot entry is a collection of options which are stored in a configuration file and tied to a particular kernel version. In practice, you have at least as many boot entries as your system has installed kernels. The boot entry configuration file is located in the /boot/loader/entries/ directory and can look like this:

6f9cc9cb7d7845d49698c9537337cedc-4.18.0-5.el8.x86_64.conf

The file name above consists of a machine ID stored in the /etc/machine-id file, and a kernel version.

The boot entry configuration file contains information about the kernel version, the initial ramdisk image, and the kernelopts environment variable, which contains the kernel command-line parameters. The example contents of a boot entry config can be seen below:

title Red Hat Enterprise Linux (4.18.0-74.el8.x86_64) 8.0 (Ootpa) version 4.18.0-74.el8.x86_64 linux /vmlinuz-4.18.0-74.el8.x86_64 initrd /initramfs-4.18.0-74.el8.x86_64.img $tuned_initrd options $kernelopts $tuned_params id rhel-20190227183418-4.18.0-74.el8.x86_64 grub_users $grub_users grub_arg --unrestricted grub_class kernel

The kernelopts environment variable is defined in the /boot/grub2/grubenv file.

Additional resources

4.3. Changing kernel command-line parameters for all boot entries

Change kernel command-line parameters for all boot entries on your system.

Prerequisites

-

Verify that the

grubbyutility is installed on your system. -

Verify that the

ziplutility is installed on your IBM Z system.

Procedure

To add a parameter:

# grubby --update-kernel=ALL --args="<NEW_PARAMETER>"For systems that use the GRUB boot loader, the command updates the

/boot/grub2/grubenvfile by adding a new kernel parameter to thekerneloptsvariable in that file.On IBM Z, update the boot menu:

# zipl

To remove a parameter:

# grubby --update-kernel=ALL --remove-args="<PARAMETER_TO_REMOVE>"On IBM Z, update the boot menu:

# zipl

Newly installed kernels inherit the kernel command-line parameters from your previously configured kernels.

Additional resources

- What are kernel command-line parameters

-

grubby(8)andzipl(8)manual pages - grubby tool

4.4. Changing kernel command-line parameters for a single boot entry

Make changes in kernel command-line parameters for a single boot entry on your system.

Prerequisites

-

Verify that the

grubbyandziplutilities are installed on your system.

Procedure

To add a parameter:

# grubby --update-kernel=/boot/vmlinuz-$(uname -r) --args="<NEW_PARAMETER>"On IBM Z, update the boot menu:

# zipl

To remove a parameter:

# grubby --update-kernel=/boot/vmlinuz-$(uname -r) --remove-args="<PARAMETER_TO_REMOVE>"On IBM Z, update the boot menu:

# zipl

On systems that use the grub.cfg file, there is, by default, the options parameter for each kernel boot entry, which is set to the kernelopts variable. This variable is defined in the /boot/grub2/grubenv configuration file.

On GRUB2 systems:

-

If the kernel command-line parameters are modified for all boot entries, the

grubbyutility updates thekerneloptsvariable in the/boot/grub2/grubenvfile. -

If kernel command-line parameters are modified for a single boot entry, the

kerneloptsvariable is expanded, the kernel parameters are modified, and the resulting value is stored in the respective boot entry’s/boot/loader/entries/<RELEVANT_KERNEL_BOOT_ENTRY.conf>file.

On zIPL systems:

-

grubbymodifies and stores the kernel command-line parameters of an individual kernel boot entry in the/boot/loader/entries/<ENTRY>.conffile.

Additional resources

- What are kernel command-line parameters

-

grubby(8)andzipl(8)manual pages - grubby tool

4.5. Changing kernel command-line parameters temporarily at boot time

Make temporary changes to a Kernel Menu Entry by changing the kernel parameters only during a single boot process.

This procedure applies only for a single boot and does not persistently make the changes.

Procedure

- Boot into the GRUB 2 boot menu.

- Select the kernel you want to start.

- Press the e key to edit the kernel parameters.

-

Find the kernel command line by moving the cursor down. The kernel command line starts with

linuxon 64-Bit IBM Power Series and x86-64 BIOS-based systems, orlinuxefion UEFI systems. Move the cursor to the end of the line.

NotePress Ctrl+a to jump to the start of the line and Ctrl+e to jump to the end of the line. On some systems, Home and End keys might also work.

Edit the kernel parameters as required. For example, to run the system in emergency mode, add the

emergencyparameter at the end of thelinuxline:linux ($root)/vmlinuz-4.18.0-348.12.2.el8_5.x86_64 root=/dev/mapper/rhel-root ro crashkernel=auto resume=/dev/mapper/rhel-swap rd.lvm.lv=rhel/root rd.lvm.lv=rhel/swap rhgb quiet emergencyTo enable the system messages, remove the

rhgbandquietparameters.- Press Ctrl+x to boot with the selected kernel and the modified command line parameters.

If you press the Esc key to leave command line editing, it will drop all the user made changes.

4.6. Configuring GRUB settings to enable serial console connection

The serial console is beneficial when you need to connect to a headless server or an embedded system and the network is down. Or when you need to avoid security rules and obtain login access on a different system.

You need to configure some default GRUB settings to use the serial console connection.

Prerequisites

- You have root permissions.

Procedure

Add the following two lines to the

/etc/default/grubfile:GRUB_TERMINAL="serial" GRUB_SERIAL_COMMAND="serial --speed=9600 --unit=0 --word=8 --parity=no --stop=1"

The first line disables the graphical terminal. The

GRUB_TERMINALkey overrides values ofGRUB_TERMINAL_INPUTandGRUB_TERMINAL_OUTPUTkeys.The second line adjusts the baud rate (

--speed), parity and other values to fit your environment and hardware. Note that a much higher baud rate, for example 115200, is preferable for tasks such as following log files.Update the GRUB configuration file.

On BIOS-based machines:

# grub2-mkconfig -o /boot/grub2/grub.cfgOn UEFI-based machines:

# grub2-mkconfig -o /boot/efi/EFI/redhat/grub.cfg

- Reboot the system for the changes to take effect.

Chapter 5. Configuring kernel parameters at runtime

As a system administrator, you can modify many facets of the Red Hat Enterprise Linux kernel’s behavior at runtime. Configure kernel parameters at runtime by using the sysctl command and by modifying the configuration files in the /etc/sysctl.d/ and /proc/sys/ directories.

Configuring kernel parameters on a production system requires careful planning. Unplanned changes may render the kernel unstable, requiring a system reboot. Verify that you are using valid options before changing any kernel values.

5.1. What are kernel parameters

Kernel parameters are tunable values which you can adjust while the system is running. There is no requirement to reboot or recompile the kernel for changes to take effect.

It is possible to address the kernel parameters through:

-

The

sysctlcommand -

The virtual file system mounted at the

/proc/sys/directory -

The configuration files in the

/etc/sysctl.d/directory

Tunables are divided into classes by the kernel subsystem. Red Hat Enterprise Linux has the following tunable classes:

Table 5.1. Table of sysctl classes

| Tunable class | Subsystem |

|---|---|

|

| Execution domains and personalities |

|

| Cryptographic interfaces |

|

| Kernel debugging interfaces |

|

| Device-specific information |

|

| Global and specific file system tunables |

|

| Global kernel tunables |

|

| Network tunables |

|

| Sun Remote Procedure Call (NFS) |

|

| User Namespace limits |

|

| Tuning and management of memory, buffers, and cache |

Additional resources

-

sysctl(8), andsysctl.d(5)manual pages

5.2. Configuring kernel parameters temporarily with sysctl

Use the sysctl command to temporarily set kernel parameters at runtime. The command is also useful for listing and filtering tunables.

Prerequisites

- Root permissions

Procedure

List all parameters and their values.

# sysctl -aNoteThe

# sysctl -acommand displays kernel parameters, which can be adjusted at runtime and at boot time.To configure a parameter temporarily, enter:

# sysctl <TUNABLE_CLASS>.<PARAMETER>=<TARGET_VALUE>The sample command above changes the parameter value while the system is running. The changes take effect immediately, without a need for restart.

NoteThe changes return back to default after your system reboots.

Additional resources

5.3. Configuring kernel parameters permanently with sysctl

Use the sysctl command to permanently set kernel parameters.

Prerequisites

- Root permissions

Procedure

List all parameters.

# sysctl -aThe command displays all kernel parameters that can be configured at runtime.

Configure a parameter permanently:

# sysctl -w <TUNABLE_CLASS>.<PARAMETER>=<TARGET_VALUE> >> /etc/sysctl.confThe sample command changes the tunable value and writes it to the

/etc/sysctl.conffile, which overrides the default values of kernel parameters. The changes take effect immediately and persistently, without a need for restart.

To permanently modify kernel parameters you can also make manual changes to the configuration files in the /etc/sysctl.d/ directory.

Additional resources

-

The

sysctl(8)andsysctl.conf(5)manual pages - Using configuration files in /etc/sysctl.d/ to adjust kernel parameters

5.4. Using configuration files in /etc/sysctl.d/ to adjust kernel parameters

Modify configuration files in the /etc/sysctl.d/ directory manually to permanently set kernel parameters.

Prerequisites

- Root permissions

Procedure

Create a new configuration file in

/etc/sysctl.d/.# vim /etc/sysctl.d/<some_file.conf>Include kernel parameters, one per line.

<TUNABLE_CLASS>.<PARAMETER>=<TARGET_VALUE><TUNABLE_CLASS>.<PARAMETER>=<TARGET_VALUE>- Save the configuration file.

Reboot the machine for the changes to take effect.

Alternatively, to apply changes without rebooting, enter:

# sysctl -p /etc/sysctl.d/<some_file.conf>The command enables you to read values from the configuration file, which you created earlier.

Additional resources

-

sysctl(8),sysctl.d(5)manual pages

5.5. Configuring kernel parameters temporarily through /proc/sys/

Set kernel parameters temporarily through the files in the /proc/sys/ virtual file system directory.

Prerequisites

- Root permissions

Procedure

Identify a kernel parameter you want to configure.

# ls -l /proc/sys/<TUNABLE_CLASS>/The writable files returned by the command can be used to configure the kernel. The files with read-only permissions provide feedback on the current settings.

Assign a target value to the kernel parameter.

# echo <TARGET_VALUE> > /proc/sys/<TUNABLE_CLASS>/<PARAMETER>The command makes configuration changes that will disappear once the system is restarted.

Optionally, verify the value of the newly set kernel parameter.

# cat /proc/sys/<TUNABLE_CLASS>/<PARAMETER>

5.6. Additional resources

Chapter 6. Making temporary changes to the GRUB menu

You can modify GRUB menu entries or pass arguments to the kernel, which applies only to the current boot. On a selected menu entry in the boot loader menu, you can:

- display the menu entry editor interface by pressing the e key.

- discard any changes and reload the standard menu interface by pressing the Esc key.

- load the command-line interface by pressing the c key.

- type any relevant GRUB commands and enter them by pressing the Enter key.

- complete a command based on context by pressing the Tab key.

- move to the beginning of a line by pressing the Ctrl+a key combination.

- move to the end of a line by pressing the Ctrl+e key combination.

The following procedures provide instruction on making changes to a GRUB Menu during a single boot process.

6.1. Introduction to GRUB

GRUB stands for the GNU GRand Unified Bootloader. With GRUB, you can select an operating system or kernel to be loaded at system boot time. Also, you can pass arguments to the kernel.

When booting with GRUB, you can use either a menu interface or a command-line interface (the GRUB command shell). When you start the system, the menu interface appears.

You can switch to the command-line interface by pressing the c key.

You can return to the menu interface by typing exit and pressing the Enter key.

GRUB BLS files

The boot loader menu entries are defined as Boot Loader Specification (BLS) files. This file format manages boot loader configuration for each boot option in a drop-in directory, without manipulating boot loader configuration files. The grubby utility can edit these BLS files.

GRUB configuration file

The /boot/grub2/grub.cfg configuration file does not define the menu entries.

Additional resources

6.2. Introduction to bootloader specification

The BootLoader Specification (BLS) defines a scheme and the file format to manage the bootloader configuration for each boot option in the drop-in directory without the need to manipulate the bootloader configuration files. Unlike earlier approaches, each boot entry is now represented by a separate configuration file in the drop-in directory. The drop-in directory extends its configuration without having the need to edit or regenerate the configuration files. The BLS extends this concept for the boot menu entries.

Using BLS, you can manage the bootloader menu options by adding, removing, or editing individual boot entry files in a directory. This makes the kernel installation process significantly simpler and consistent across the different architectures.

The grubby tool is a thin wrapper script around the BLS and it supports the same grubby arguments and options. It runs the dracut to create an initial ramdisk image. With this setup, the core bootloader configuration files are static and are not modified after kernel installation.

This premise is particularly relevant in RHEL 8, because the same bootloader is not used in all architectures. GRUB is used in most of them such as the 64-bit ARM, but little-endian variants of IBM Power Systems with Open Power Abstraction Layer (OPAL) uses Petitboot and the IBM Z architecture uses zipl.

Additional Resources

- Section 4.2, “Understanding boot entries”

-

the

grubby(8)manual page

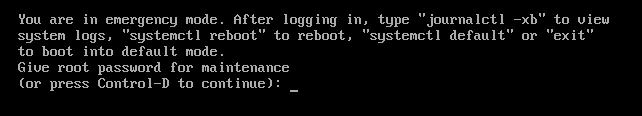

6.3. Booting to rescue mode

Rescue mode provides a convenient single-user environment in which you can repair your system in situations when it is unable to complete a normal booting process. In rescue mode, the system attempts to mount all local file systems and start some important system services. However, it does not activate network interfaces or allow more users to be logged into the system at the same time.

Procedure

- On the GRUB boot screen, press the e key for edit.

Add the following parameter at the end of the

linuxline:systemd.unit=rescue.target

Press Ctrl+x to boot to rescue mode.

6.4. Booting to emergency mode

Emergency mode provides the most minimal environment possible in which you can repair your system even in situations when the system is unable to enter rescue mode.

In emergency mode, the system:

-

mounts the

rootfile system only for reading - starts a few essential services

However, the system does not:

- attempt to mount any other local file systems

- activate network interfaces

Procedure

- On the GRUB boot screen, press the e key for edit.

Add the following parameter at the end of the

linuxline:systemd.unit=emergency.target

Press Ctrl+x to boot to emergency mode.

6.5. Booting to the debug shell

The systemd debug shell provides a shell very early in the start-up process. Once in the debug shell, you can use the systemctl commands, such as systemctl list-jobs and systemctl list-units, to search for the cause of systemd related boot-up problems.

Procedure

- On the GRUB boot screen, press the e key for edit.

Add the following parameter at the end of the

linuxline:systemd.debug-shell

Optionally add the

debugoption.NoteAdding the

debugoption to the kernel command line increases the number of log messages. Forsystemd, the kernel command-line optiondebugis now a shortcut forsystemd.log_level=debug.- Press Ctrl+x to boot to the debug shell.

Permanently enabling the debug shell is a security risk because no authentication is required to use it. Disable it when the debugging session has ended.

6.6. Connecting to the debug shell

During the boot process, the systemd-debug-generator configures the debug shell on TTY9.

Prerequisites

- You have booted to the debug shell successfully. See Booting to the debug shell.

Procedure

Press Ctrl+Alt+F9 to connect to the debug shell.

If you work with a virtual machine, sending this key combination requires support from the virtualization application. For example, if you use Virtual Machine Manager, select Send Key →

Ctrl+Alt+F9from the menu.- The debug shell does not require authentication, therefore you can see a prompt similar to the following on TTY9:

sh-4.4#

Verification steps

Enter a command as follows:

sh-4.4# systemctl status $$

- To return to the default shell, if the boot succeeded, press Ctrl+Alt+F1.

Additional resources

-

The

systemd-debug-generator(8)manual page

6.7. Resetting the root password using an installation disk

In case you forget or lose the root password, you can reset it.

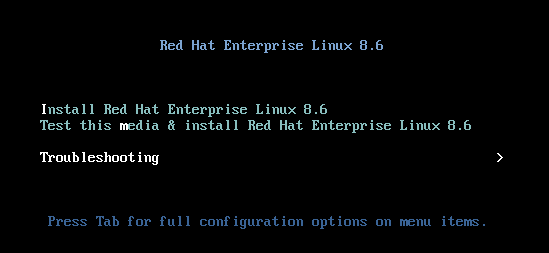

Procedure

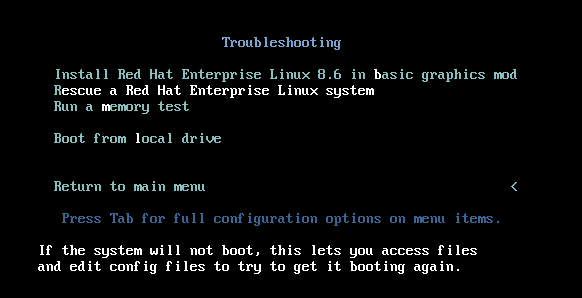

- Boot the host from an installation source.

In the boot menu for the installation media, select the

Troubleshootingoption.

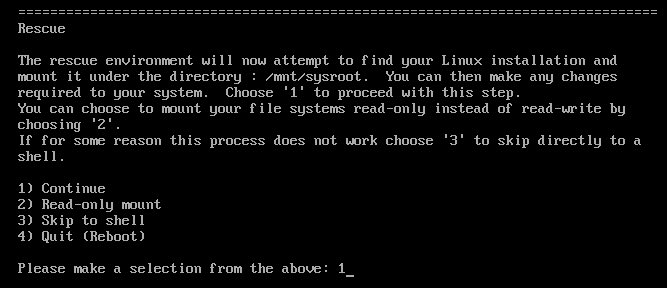

In the Troubleshooting menu, select the

Rescue a Red Hat Enterprise Linux systemoption.

At the Rescue menu, select

1and press the Enter key to continue.

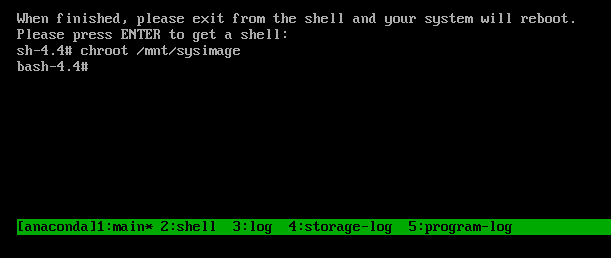

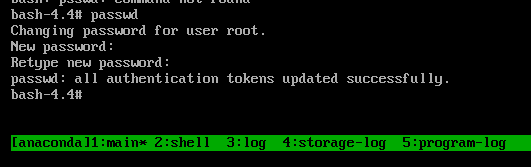

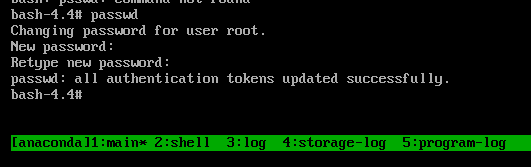

Change the file system

rootas follows:sh-4.4# chroot /mnt/sysimage

Enter the

passwdcommand and follow the instructions displayed on the command line to change therootpassword.

Remove the

autorelablefile to prevent a time consuming SELinux relabel of the disk:sh-4.4# rm -f /.autorelabel

-

Enter the

exitcommand to exit thechrootenvironment. -

Enter the

exitcommand again to resume the initialization and finish the system boot.

6.8. Resetting the root password using rd.break

In case you forget or lose the root password, you can reset it.

Procedure

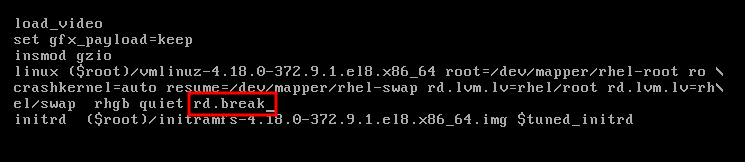

- Start the system and, on the GRUB boot screen, press the e key for edit.

Add the

rd.breakparameter at the end of thelinuxline:

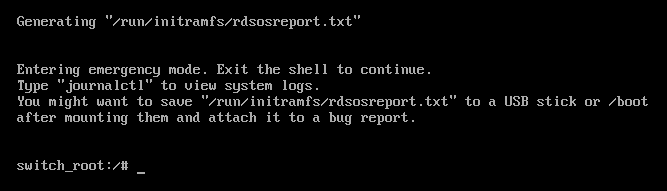

Press Ctrl+x to boot the system with the changed parameters.

Remount the file system as writable.

switch_root:/# mount -o remount,rw /sysrootChange the file system’s

root.switch_root:/# chroot /sysrootEnter the

passwdcommand and follow the instructions displayed on the command line.

Relabel all files on the next system boot.

sh-4.4# touch /.autorelabelRemount the file system as read only:

sh-4.4# mount -o remount,ro /-

Enter the

exitcommand to exit thechrootenvironment. Enter the

exitcommand again to resume the initialization and finish the system boot.NoteThe SELinux relabeling process can take a long time. A system reboot occurs automatically when the process is complete.

You can omit the time consuming SELinux relabeling process by adding the enforcing=0 option.

Procedure

When adding the

rd.breakparameter at the end of thelinuxline, appendenforcing=0as well.rd.break enforcing=0

Restore the

/etc/shadowfile’s SELinux security context.# restorecon /etc/shadowTurn SELinux policy enforcement back on and verify that it is on.

# setenforce 1 # getenforce Enforcing

Note that if you added the enforcing=0 option in step 3 you can omit entering the touch /.autorelabel command in step 8.

6.9. Additional resources

-

The

/usr/share/doc/grub2-commondirectory. -

The

info grub2command.

Chapter 7. Making persistent changes to the GRUB boot loader

Use the grubby tool to make persistent changes in GRUB.

7.1. Prerequisites

- You have successfully installed RHEL on your system.

- You have root permission.

7.2. Listing the default kernel

By listing the default kernel, you can find the file name and the index number of the default kernel to make permanent changes to the GRUB boot loader.

Procedure

- To find out the file name of the default kernel, enter:

# grubby --default-kernel

/boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64- To find out the index number of the default kernel, enter:

# grubby --default-index

07.3. Viewing the GRUB menu entry for a kernel

You can list all the kernel menu entries or view the GRUB menu entry for a specific kernel.

Procedure

To list all kernel menu entries, enter:

# grubby --info=ALL index=0 kernel="/boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64" args="ro crashkernel=auto resume=/dev/mapper/rhel-swap rd.lvm.lv=rhel/root rd.lvm.lv=rhel/swap rhgb quiet $tuned_params zswap.enabled=1" root="/dev/mapper/rhel-root" initrd="/boot/initramfs-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64.img $tuned_initrd" title="Red Hat Enterprise Linux (4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64) 8.6 (Ootpa)" id="67db13ba8cdb420794ef3ee0a8313205-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64" index=1 kernel="/boot/vmlinuz-0-rescue-67db13ba8cdb420794ef3ee0a8313205" args="ro crashkernel=auto resume=/dev/mapper/rhel-swap rd.lvm.lv=rhel/root rd.lvm.lv=rhel/swap rhgb quiet" root="/dev/mapper/rhel-root" initrd="/boot/initramfs-0-rescue-67db13ba8cdb420794ef3ee0a8313205.img" title="Red Hat Enterprise Linux (0-rescue-67db13ba8cdb420794ef3ee0a8313205) 8.6 (Ootpa)" id="67db13ba8cdb420794ef3ee0a8313205-0-rescue"To view the GRUB menu entry for a specific kernel, enter:

# grubby --info /boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64 grubby --info /boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64 index=0 kernel="/boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64" args="ro crashkernel=auto resume=/dev/mapper/rhel-swap rd.lvm.lv=rhel/root rd.lvm.lv=rhel/swap rhgb quiet $tuned_params zswap.enabled=1" root="/dev/mapper/rhel-root" initrd="/boot/initramfs-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64.img $tuned_initrd" title="Red Hat Enterprise Linux (4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64) 8.6 (Ootpa)" id="67db13ba8cdb420794ef3ee0a8313205-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64"

Try tab completion to see available kernels within the /boot directory.

7.4. Editing a Kernel Argument

You can change a value in an existing kernel argument. For example, you can change the virtual console (screen) font and size.

Procedure

Change the virtual console font to

latarcyrheb-sunwith the size of32.# grubby --args=vconsole.font=latarcyrheb-sun32 --update-kernel /boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64

7.5. Adding and removing arguments from a GRUB menu entry

You can add, remove, or simultaneously add and remove arguments from the GRUB Menu.

Procedure

To add arguments to a GRUB menu entry, use the

--update-kerneloption in combination with--args. For example, following command adds a serial console:# grubby --args=console=ttyS0,115200 --update-kernel /boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64The console arguments are attached to the end of the line, the new console will take precedence over any other configured consoles.

To remove arguments from a GRUB menu entry, use the

--update-kerneloption in combination with--remove-args. For example:# grubby --remove-args="rhgb quiet" --update-kernel /boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64This command removes the Red Hat graphical boot argument and enables log messages, that is verbose mode.

To add and remove arguments simultaneously, enter:

# grubby --remove-args="rhgb quiet" --args=console=ttyS0,115200 --update-kernel /boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64

Verification steps

To review the permanent changes you have made, enter:

# grubby --info /boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64 index=0 kernel="/boot/vmlinuz-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64" args="ro crashkernel=auto resume=/dev/mapper/rhel-swap rd.lvm.lv=rhel/root rd.lvm.lv=rhel/swap $tuned_params zswap.enabled=1 console=ttyS0,115200" root="/dev/mapper/rhel-root" initrd="/boot/initramfs-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64.img $tuned_initrd" title="Red Hat Enterprise Linux (4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64) 8.6 (Ootpa)" id="67db13ba8cdb420794ef3ee0a8313205-4.18.0-372.9.1.el8.x86_64"

7.6. Adding a new boot entry

You can add a new boot entry to the bootloader menu entries.

Procedure

Copy all the kernel arguments from your default kernel to this new kernel entry.

# grubby --add-kernel=new_kernel --title="entry_title" --initrd="new_initrd" --copy-defaultGet the list of available boot entries.